You Should Read CLEAR by Carys Davies

Reading Notes

The first six weeks of school nearly trampled me. I’m enjoying my courses and students, but the current paces has had me second-guessing myself on more than one lonely midnight. (By “midnight” I mean “the brief window between dinner and bedtime when I have a moment to myself,” because who am I kidding? I’m barely awake past nine.)

My “to do” list has a “to do” list of its own, complete with tabs and missed deadlines and a color coding system I can no longer decipher. My grading pile regenerates like the tail of the newt we had as a class pet in Mr. Thomas’s second grade.1 My house—well. I’ve decided the level of clutter in my house is easier to accept if I think of the kicked-off shoes and overdue library books as artifacts in the Museum of Modern Life. I can hear the tour guide’s voice now: And here we have the kitchen, complete with authentic spaghetti-and-meatball-encrusted plates that never made their way to the dishwasher. I can picture the postcards sold in the gift shop, with neat and tidy captions on the back: A waterfall of clean laundry spills from the dryer to the dirty floor, not a free laundry basket in sight.

What’s that, you say? Your life is spinning out of your hands, too?

Then allow me to present the perfect antidote: Clear by Carys Davies.

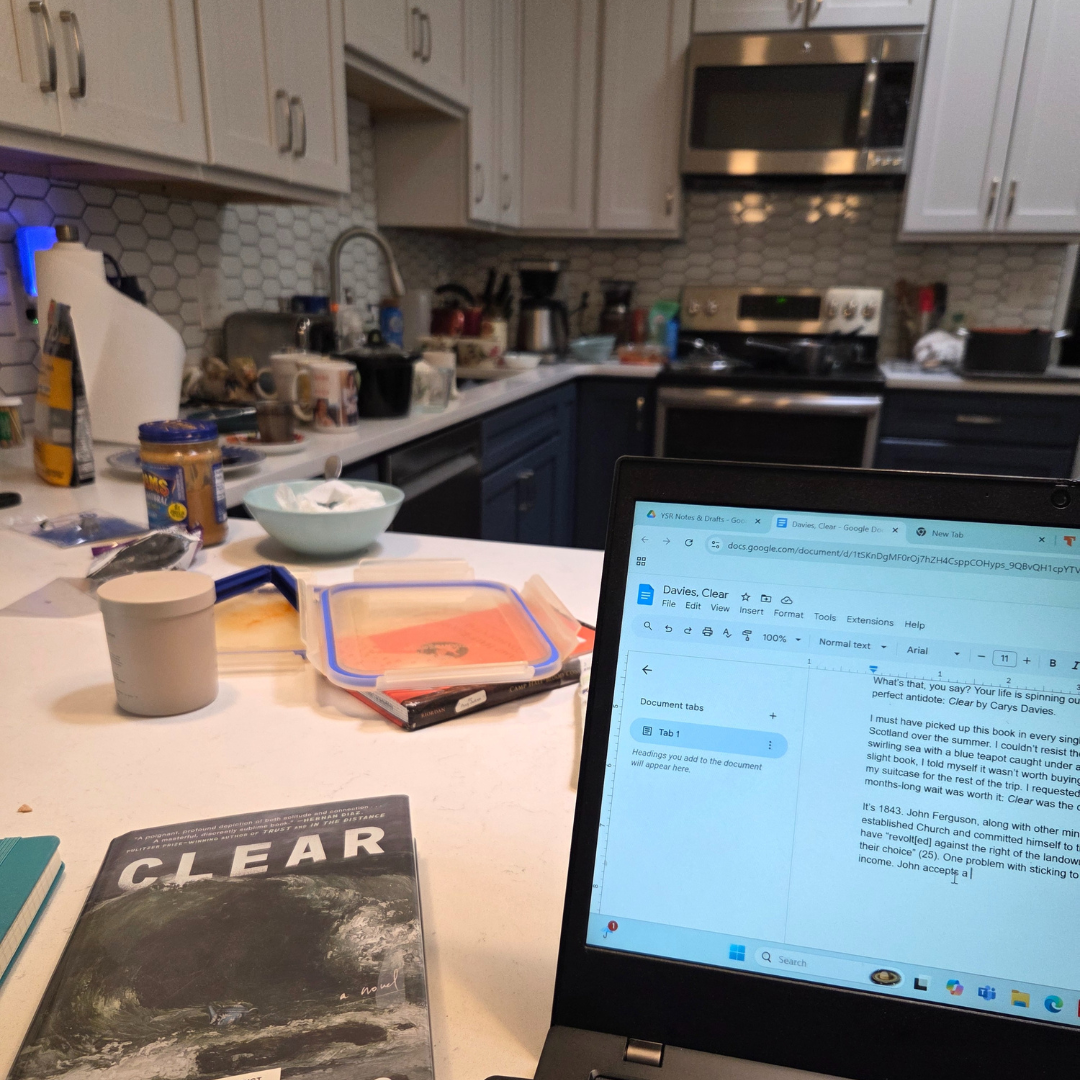

This sad picture of my library copy does not do justice to Tristan Offit’s beautiful cover art

It’s 1843. John Ferguson, along with other ministers across Scotland, has renounced the established Church. Committed to the new Free Church, John and his brethren have “revolt[ed] against the right of the landowners . . . to confer clerical livings on ministers of their choice” (25). One problem with sticking to your principles, John discovers, is losing your income. Desperate, he accepts a job working for Henry Lowrie, a wealthy landowner who tasks John with traveling to an out-of-the-way island and informing its single occupant, Ivar, that he must leave his lifelong home because the Lowries want to make some money raising sheep there.

Mary, John’s wife, has her doubts. He assures her it’s a harmless endeavor, a necessary and temporary means to their Free Church end. But soon after arriving on the island, before he has a chance to find its lone inhabitant, he suffers an accident. Unconscious, he’s found and tended to by Ivar. By the time John regains his faculties and realizes who his caretaker is, it’s too late to tell the truth about his mission.

Their misunderstanding extends beyond their situation. Ivar speaks a dying language that John has never heard and cannot interpret. Convalescing in Ivar’s home, John takes diligent notes during their conversations so he can create a makeshift dictionary. As he recovers and ventures outside, their vocabulary expands and their exchanges deepen:

“Everything had become fairly lively since they’d begun adding verbs and adverbs to the nouns in the makeshift blue dictionary—lots of moving around and lots of arm waving on Ivar’s part and as much as John Ferguson could manage with his bruised and possibly cracked ribs; lots of nodding and headshaking, too, and a succession of pantomimes and charades as John Ferguson mimed what it was he wanted to know, and Ivar acted out what he was trying to describe, and between them they inched toward the right words for, say, knitting and spinning and carding the wool; for eating quietly and for eating noisily; for walking quickly and for walking slowly; for shouting and for whispering; for jumping and for shivering; for coughing and sneezing; for crouching by the fire and for shooing away the hens.”

Since the rest of his family departed for Canada years ago, Ivar has lived on the island by himself. Until John’s arrival, though, Ivar has “not thought of himself as being lonely, or even alone” (84). He has his cow, Pegi, and his simple home and his intuitive knowledge of the windswept island. But while John sleeps, Ivar examines the dictionary and experiences a spark of wonder:

“Before the arrival of John Ferguson, he’d never really thought of the things he saw or heard or touched or felt as words. . . . He wondered, looking at the column of words, none of which he could read—neither the ones on the left in John Ferguson’s tongue nor the ones on the right in his own—if there was a word in John Ferguson’s language for the excitement he felt when he ran his finger down the line between the two columns of words, which seemed to him to connect their lives in the strongest possible way—words for ‘milk’ and ‘stream’ and the flightless blue-winged beetle that lived in the hill pasture; words for ‘halibut’ and ‘byre’ and the overhand knot he used in the cow’s tether; words for ‘house’ and ‘butter,’ for ‘heather’ and ‘whey,’ for ‘sea wrack’ and ‘chicken.’ It was as if he’d never fully understood his solitude until now.”

Ivar regards John’s handwritten dictionary almost like a magic spell. Words do that to us, don’t they? I see Ivar dangling over the edge of a cliff, held by a handwoven rope as he hunts for seabird eggs. I feel his humble regard for the land that sustains him. I understand his wonder at communicating with a total stranger. Here I am, typing away on a Sunday in my messy kitchen, ignoring all of my to-do’s because I can’t get Davies’ words out of my head, because I have so many words I want to share with you.

Welcome to the Kitchen Exhibit in the Museum of Modern Life

Davies writes, “There is a word in Ivar’s language for the moment before something happens; for the state of being on the brink of something” (167). This sentence precisely captures the mood of the book’s gorgeous, broody cover art, which features a swirling sea with a blue teapot caught under a crashing wave, but for me, the sentence also offers a mindset shift as I head into autumn.

Making a “to do” list is another way of telling myself that I must be doing, accomplishing, producing all the time. But I don’t! Neither do you! Sometimes we can just enjoy “being on the brink,” floating on the wild sea in the moment before the wave envelops us.

Last Thursday, absolutely nothing out of the ordinary occurred, and I had the most fantastic day at school. Both my lessons and my students worked, and I went home thinking, “I am so lucky to teach.” I wished, like Ivar, I had a word to convey the entirety of what I felt—trampled, yet exhilarated—but then I sat down to write about Clear and realized that Davies’ novel does a better job than any single word could.

Clear reminds us that our connections with others are most fulfilling when we detach our relationships from expectations, when we communicate with wonder instead of judgment, when we tell our “to do” lists to wait a while longer.

If you find yourself in need of respite and rejuvenation, you should read Clear.

Need-to-Know

Pub Date: 2025

Timeline: About a month in 1843

Narrator: Close third POV among three characters

Length: 185 pages; audiobook runs about 3 hours

Pairs Well With: The Place of Tidesby James Rebanks; Twist by Colum McCann; Foster by Claire Keegan; sojourns on remote islands; hikes along a cliff

Book Club

Mary, concerned at her husband’s lack of communication, undertakes a journey to find him, and her arrival forces Ivar and John to confront the reality of John’s visit and the truth of their relationship. How did you react to the ending? What did you expect to happen? If you were Mary, how would you have responded?

John’s homemade dictionary is a revelation for Ivar: “Before the arrival of John Ferguson, [Ivar hard] never really thought of the things he saw or heard or touched or felt as words. In the old days, the minister had read to them from the Bible in a language they didn’t understand, and then shouted at them in a terrible approximation of their own tongue. But it was strange to think of a fine sea mist, say, or the cold northeasterly wind that came in spring and damaged the corn as solid things on a piece of paper you could touch.” What’s your favorite word? Why? Is the sound or the meaning more important?

Close Reading

As the summer reaches its height, the island spends most of the day in sunlight:

“At this time of year, when it is light for so much of the night, the island feels like an unsleeping place, as if it is only ever dozing through the small hours and nothing could happen anywhere on it, or around it, without it noticing.”

The word “dozing” seems to personify the island, but Davies specifically compares the island to an “unsleeping place,” not an unsleeping person. The deliberate choice not to personify the island acknowledges it as a living being, while keeping it separate from humans. This mirrors Ivar’s relationship with the land.

While he knows the place well, he struggles to survive in some seasons. Unlike Lowrie, Ivar’s absent landlord, Ivar does not try to impose his will on the island. Lowrie may have plans to drop off a flock of sheep there and send someone to collect their wool (and accompanying money) once a year, but Ivar knows that the land can’t be controlled so easily. Those last three words, “without it noticing,” hold a warning for anyone who tries to best the land.

Creative Writing

Fiction: Davies writes about “a word in Ivar’s language for the moment before something happens; for the state of being on the brink of something.” Although it takes a while for Ivar to convey its meaning, eventually John “arrive[s] at a precise and succinct definition of it—a definition in which he will give, as examples of the sort of moment it describes, ‘the last moment before the tide turns; the last moment of day before night begins’” (167). Open a dictionary at random. Look for the first word you don’t know. Use its definition as a starting point. Maybe it suggests a certain setting or atmosphere; maybe it’s something a character needs to know or do.

Nonfiction: Reflecting on his solitary life, Ivar insists that he never felt lonely. However, he admits to himself that “isn’t to say he didn’t feel a little low when summer began to give way to the slow beginning of winter; when it was the end of the short nights and the beginning of the long ones, when most of the birds were gone and the geese had not yet arrived” (84-5). Choose a seasonal transition (spring to summer, summer to fall, and so on) to write about. Start with imagery and capture this moment with your five senses. Then reflect inward. How does this in-between time make you feel?

Sentence Study

Shortly after arriving on the island, John sets out to explore:

“The day was clear with only a low line of cloud over the horizon, and if you’d been up in the sky that morning above the island with the gannets and the guillemots, the puffins and the cormorants and the oystercatchers, you would have seen his tiny black figure leaving the Baillie house and making its way across patches of pink thrift and lush green pasture.”

This sentence is the beginning of a beautiful paragraph that begs to be reread. Although the book is narrated in a close third point-of-view, Davies shifts into second here for a moment. She sets up a hypothetical situation with that “if” and then invites the reader to populate that scene in the next word: “you’d.” We often describe an omniscient third point-of-view as “God-like,” but Davies undercuts that assumption by placing us “above the island” with all the seabirds.

John himself loses his identity here. While he’s first referred to by “his tiny black figure,” by the end of the sentence he’s been relegated to an impersonal it. Yes, “its” is the proper possessive pronoun for the antecedent “figure,” but it creates distance between the readers and John. For the length of this paragraph, we (as the “you”) associate more with the birds than with John. It’s a reminder that John is well out of his element on this tiny island.